A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research

Like many other fields within ecology, the study of organismal movement (usually – but not always – the movement of animals) lends itself naturally to multi-scale questions. As Nathan et al. (2008) summarize in their proposed framework for the analysis of animal movement data, questions about organismal movement fall into four general categories: (i) why move? (ii) how to move? (iii) when and where to move? and (iv) what are the ecological and evolutionary consequences of movement?. Though often addressed independently, each of these questions occurs on a different spatial and/or temporal scale. At the same time, the answers to all four questions are linked through physiology, internal state, and environmental factors, and together they produce an organism’s lifetime movement path. Nathan et al. propose a comprehensive multi-scale framework through which to integrate these questions.

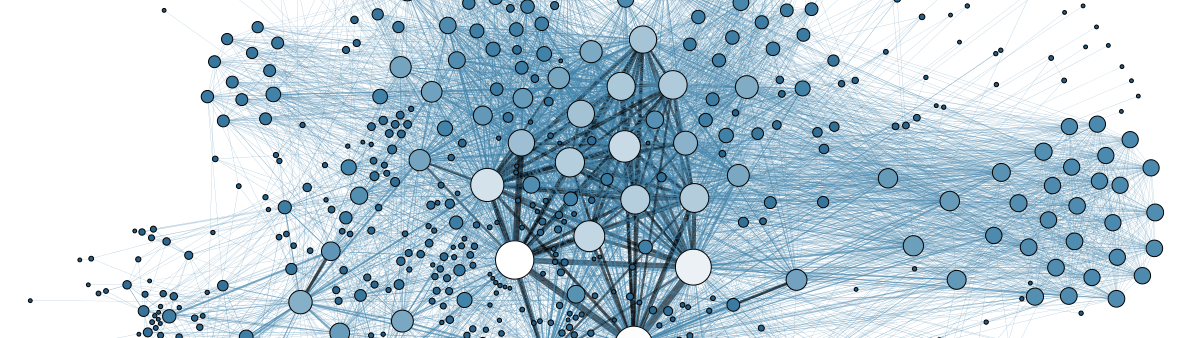

Primarily, the authors propose that a movement path can be broken down into its most basic elements, which are a sequence of steps (usually determined by the resolution at which the movements are tracked by researchers), the equivalent of genes in a DNA sequence. At a coarser scale, these steps can be aggregated into movement phases (e.g., foraging, resting, dispersal), which the authors argue are comparable to genes. Theses phases may be further grouped into different parts of an organism’s life history, for instance growth, migration, or reproduction, each of which may be made up of characteristic combination of movement modes (see Figure 1 below).

To answer the basic questions of movement ecology (as summarized above), these levels of organization – steps, phases, and tracks – can be combined using a multi-level approach. For instance, the authors propose that each step in a movement track is a function of the organism’s internal state at a given time, its motion capacity, its navigation capacity, and the environmental conditions at that place and time. These parameters produce each step, and many movement steps come together to form a movement phase, which is determined by these same parameters, but on a different scale. For instance, an animal’s decision about whether to switch from foraging to resting may depend on its internal state (e.g. hunger), which is a function of outcome of a movement on the step level (e.g. whether that step resulted in acquisition of food resources). The same logic applies to the transition between movement phases and movement tracks over longer time scales (e.g. the decision to initiate migration or reproduction may depend on total food acquisition over the previous season). By integrating these multiple levels, we can gain a better understanding of the mechanistic underpinnings – both the drivers and the constraints – of animal movement patterns.

Conceptual illustration of the different scales of an individual’s movement track. (Figure 1 in Nathan et al. 2008)

Nathan, R., Getz, W. M., Revilla, E., Holyoak, M., Kadmon, R., Saltz, D., & Smouse, P. E. (2008). A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(49), 19052-19059. http://www.pnas.org/content/105/49/19052